An Overview of "The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious" by Carl Jung

“The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious” is a collection of essays written by Carl Jung (1875-1961), founder of analytical psychology and expert on mythology and religion. Jung believed that “In addition to our immediate consciousness… there exists a second psychic system of a collective, universal, and impersonal nature which is identical in all individuals,” (Jung, 43), which he called the ‘collective unconscious’. This collective unconscious further consists of “archetypes” which are “patterns of instinctual behavior” (Jung, 44), each of which functions like “a psychic organ present in all of us” (Jung, 160). Archetypes, he asserted, could not be directly observed but only perceived. They are not the psyche itself but rather representations of it, similar to the way a painting of a landscape is not the landscape itself, though it may capture its essence. Furthermore, as inherited sets of cognitive processes, each archetype demonstrates itself similarly across cultures at different times and places, specifically in mythology and folktales, in the form of characters, symbols, and motifs. Jung believed that by analyzing the these recurring archetypes he could come to a better understanding of the human psyche and its functions.

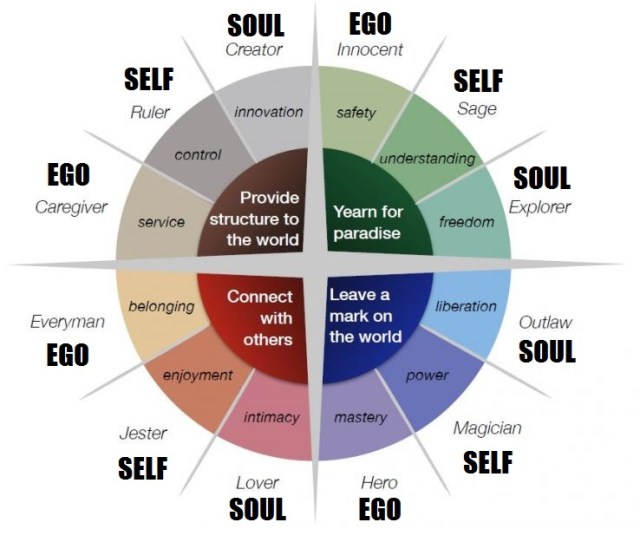

Taxonomy of distinct archetypes and their defining characterstics

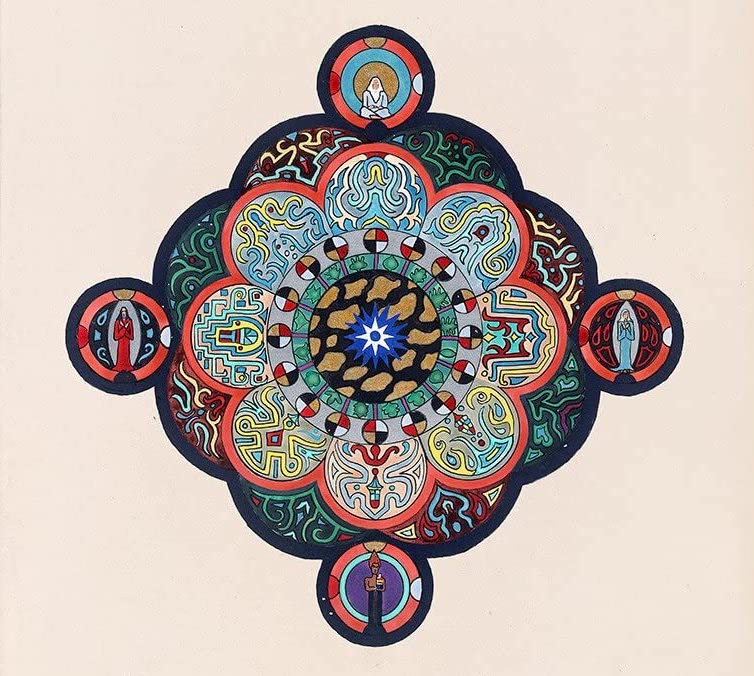

The collective unconscious can therefore be described as a set of cognitive instincts or processes, known as archetypes, which are biologically inherited and common to all people. Archetypes may represent themselves in many ways, although they often show up as personalities or characters within folkloric or religious stories. For example, Jung examines ‘the Wise Old Man’, ‘the Mother’, and ‘the Trickster’ mythological figures within his book, and also discusses archetypal symbols such as the mandala, which he describes as “the psychological expression of the totality of the self” (Jung, 304). Jung further asserts that “there are as many archetypes as there are typical situations in life,” (Jung, 48) and that each “has a positive and a negative aspect” (Jung, 37). For example, the Mother archetype may include “all that cherishes and sustains, that fosters growth and fertility” on the positive side, while connoting “anything that devours, seduces, and poisons, that is terrifying and inescapable like fate” on the negative side (Jung, 82). Essentially, each archetype may be thought of as a sort of window into the psyche where various sorts of cognitive processes may be observed and interpreted. However, “no archetype can be reduced to a simple formula. It is a vessel which we can never empty, and never fill… it persists throughout the ages and requires interpreting ever anew” (Jung, 179). While there is no absolute definition for each archetype, they tend to share many characteristics across cultures and individual minds. This is why Jung believed that it was a “great mistake to suppose that the psyche of a new-born child is a tabula rasa in the sense that there is nothing in it” (Jung, 66), as the evidence of archetypes rather suggests that the psyche is biologically programmed with preset processes which represent themselves similarly across distinct times, places, and cultures.

Mandalas, Jung thought, are an archetype that represents the psychic processes of unity and recentering, as they “mostly appear in connection with chaotic psychic states of disorientation or panic” (Jung, 360) and have a healing, reordering effect on the individual.

The psychic processes which make up the archetypes and the collective unconscious, Jung argued, are instinctual and essential to psychic wholeness and wellbeing. “When a situation occurs which corresponds to a given archetype,” he states, “that archetype becomes activated and a compulsiveness appears, which, like an instinctual drive, gains its way against all reason and will, or else produces a conflict of pathological dimensions” (Jung, 48). In other words, when archetypes are suppressed–when their cognitive processes are denied expression–they create an unresolved compulsion that causes psychic frustration, disorder, and mental illness. They slip out of the individual’s awareness, into the unconscious, where they are projected out onto the outer world, so that they may be perceived and made conscious again. Jung describes projection as the “unconscious, automatic process whereby a content that is unconscious to the subject transfers itself to an object, so that it seems to belong to that object” (Jung, 60). This process of projection allows the psyche to observe, and understand itself through the form of archetypes. That is to say, “(archetypes) are the symbolic expressions of the inner, unconscious drama of the psyche which becomes accessible to man’s consciousness by way of projection–that is, mirrored in the events of nature” (Jung, 6). In other words, the manifestation of archetypes in the form of symbols, characters, etc. is the process by which the unconscious mind comes to know and understand itself. In order to become psychologically whole, “Our task is not, therefore, to deny the archetype, but to dissolve the projections, in order to restore their contents to the individual who has involuntarily lost them by projecting them outside himself” (Jung, 84). Essentially, the dissolution of projections is a byproduct of integrating the archetypes in a conscious manner.

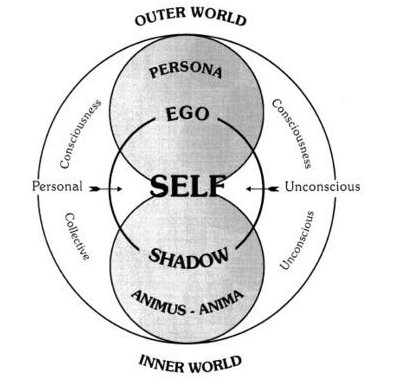

Jung's Model of the Psyche

Ultimately, Jung’s ideas on the archetypes and the collective unconsciousness point toward this process of integrating the archetypes, “the process by which a person become a psychological ‘in-dividual’, that is, a separate, indivisible unity or ‘whole’” (Jung, 275), which Jung called “individuation”. This process of individuation is a never-ending process by which an individual incorporates more and more parts of their psyche within their sense of self, their ego. The concept of ‘shadow work’ is an example of this. Shadow work involves integrating the shadow archetype, the archetype which “personifies everything that the subject refuses to acknowledge about himself””(Jung, 284). Jung asserts, however, that the archetypes “cannot be integrated simply by rational means, but require a dialectical procedure, a real coming to terms with them” (Jung, 41). Thus it is unclear exactly how an individual is to integrate their archetypes, though it can be presumed that first they must be acknowledged, understood, and expressed consciously–that is with intention rather than compulsion. Moreover, Jung argued that the more unconscious an archetype, the stronger its projection and difficulty for integration. For example, Jung thoroughly discusses the concept of the anima/animus, which he calls the archetypes “of life itself”. According to Jung, the anima is “the feminine unconscious of a man (which) is projected upon a feminine partner”, while the animus is “the masculine unconscious of a woman (that) is projected upon a man” (Jung, 177). Therefore, in order to properly integrate his anima, a man must be willing to acknowledge and utilize the feminine aspects of himself, which is a difficult process as it will challenge his very concept and identity of being a man. However, it is ultimately through this process that he becomes more psychologically whole. “If the encounter with the shadow is the ‘apprentice-piece’ in the individual’s development, then that with the anima is the ‘master-piece’” (Jung, 29), he states. This is because while the ‘shadow’ exists on a personal level and is moreso the result of individual experience, the anima/animus has been inherited by the collective, and thus exists deeper within the unconscious.

The “syzygy” motif which represents the psychological union of both masculine and feminine characteristics

Fundamentally, Jung argued that “counsciousness can only exist through continual recognition of the unconscious” (Jung, 96) and that “the uniqueness of the psyche can never enter wholly into reality, it can only be realized approximately” (Jung, 173). That is to say that the psyche can never be fully understood, only perceived to the best of our ability. “Interepretations are only for those who don’t understand,” he states, “it is only the things we don’t understand that have any meaning” (Jung, 31). Although the concepts of the collective unconscious and the archetypes stand as compelling theories for understanding the psyche and oneself, it is important to understand them only as such, theories. “Not for a moment dare we succumb to the illusion that an archetype can be finally explained and disposed of. Even the best attempts at explanation are only more or less successful translations into another language. The most we can do is to dream the myth onwards and give it a modern dress.” (Jung, 160). Ultimately, it is the continual process of uncovering and interpreting the unconscious that makes life and the path towards individuation meaningful.

SOURCE: Jung, C. G. (1968). The archetypes and the collective unconscious (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1959)

Some interpretations of 12 distinct archetypes and the relations amongst them, taken from “Understanding Personality: the 12 Jungian Archetypes”.